Review: Deep Learning In Drug Discovery

Deep learning algorithms have achieved a state of the art performance in a lot of different tasks. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) can be used to achieve considerable performance in image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation tasks. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their descendants like LSTMs and GRUs are the first things that come to mind to tackle problems like neural language translation, speech recognition, and even they are used to generate new texts and music.

Drug discovery is one of the areas that can gain a significant benefit from this success of deep learning. Drug discovery is a very time-consuming and expensive task, and machine learning (including deep learning) has the potential to make this process faster and cheaper. Recently, lots of papers have been published around this topic, and in this post, I am going to present a detailed review to see how it is possible to use deep learning in this domain.

Note: I updated this post a little bit at Feb 2020 to add recent works.

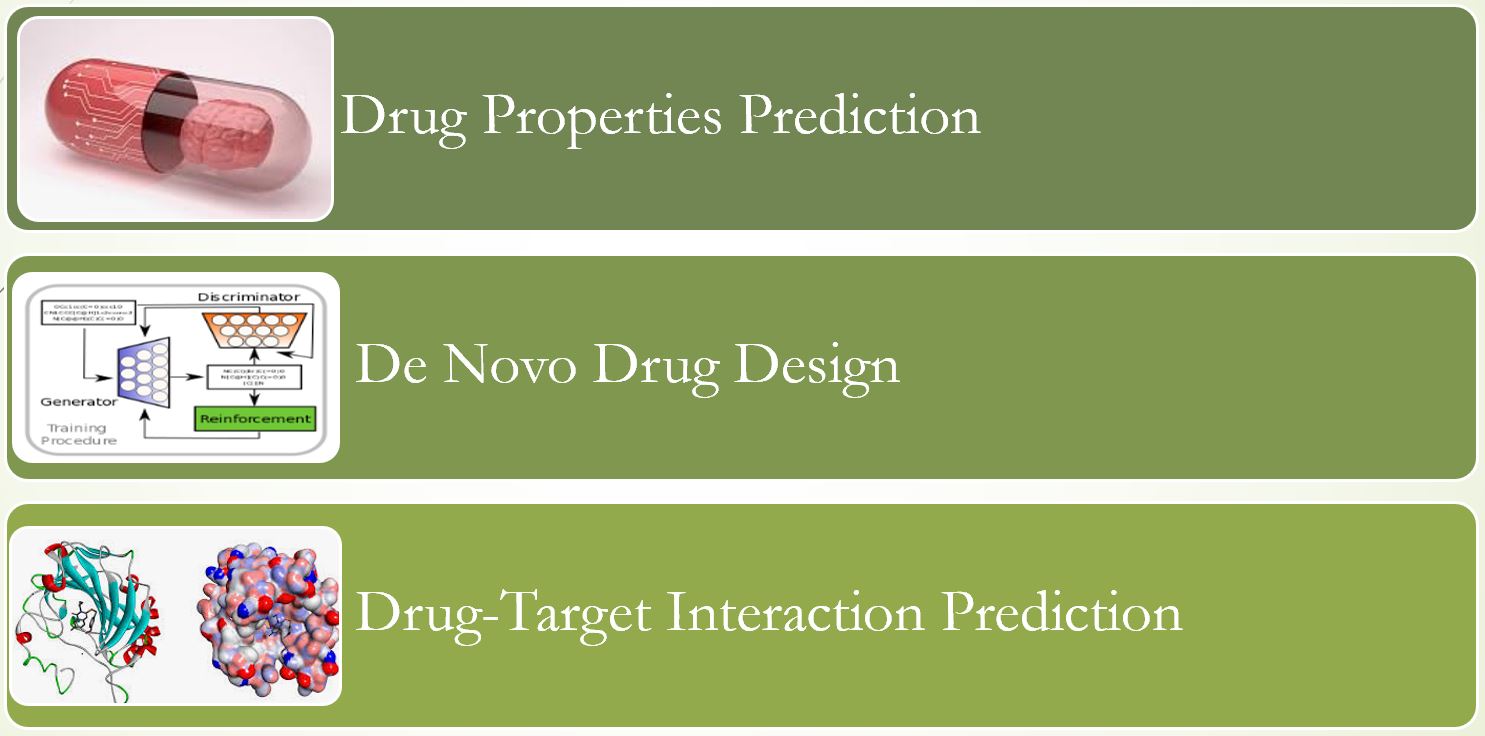

I can divide the application of deep learning in drug discovery mainly into three different categories:

- Drug properties prediction

- De Novo drug design

- Drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction

In the following, I am trying to elaborate more on each category and discuss some relevant papers.

Drug properties prediction

Machine learning problems broadly are classified into three subgroups: supervised learning, unsupervised learning (self-supervised learning), and reinforcement learning. Drug properties prediction can be framed as a supervised learning problem. The input to the algorithms is a drug (compound), and the output is drug property (e.g., drug toxicity or solubility).

- Input: A drug (small molecule)

- output: 0-1 label to indicate whether a drug has certain properties or not. It can also be framed as a multi-label classification or regression task.

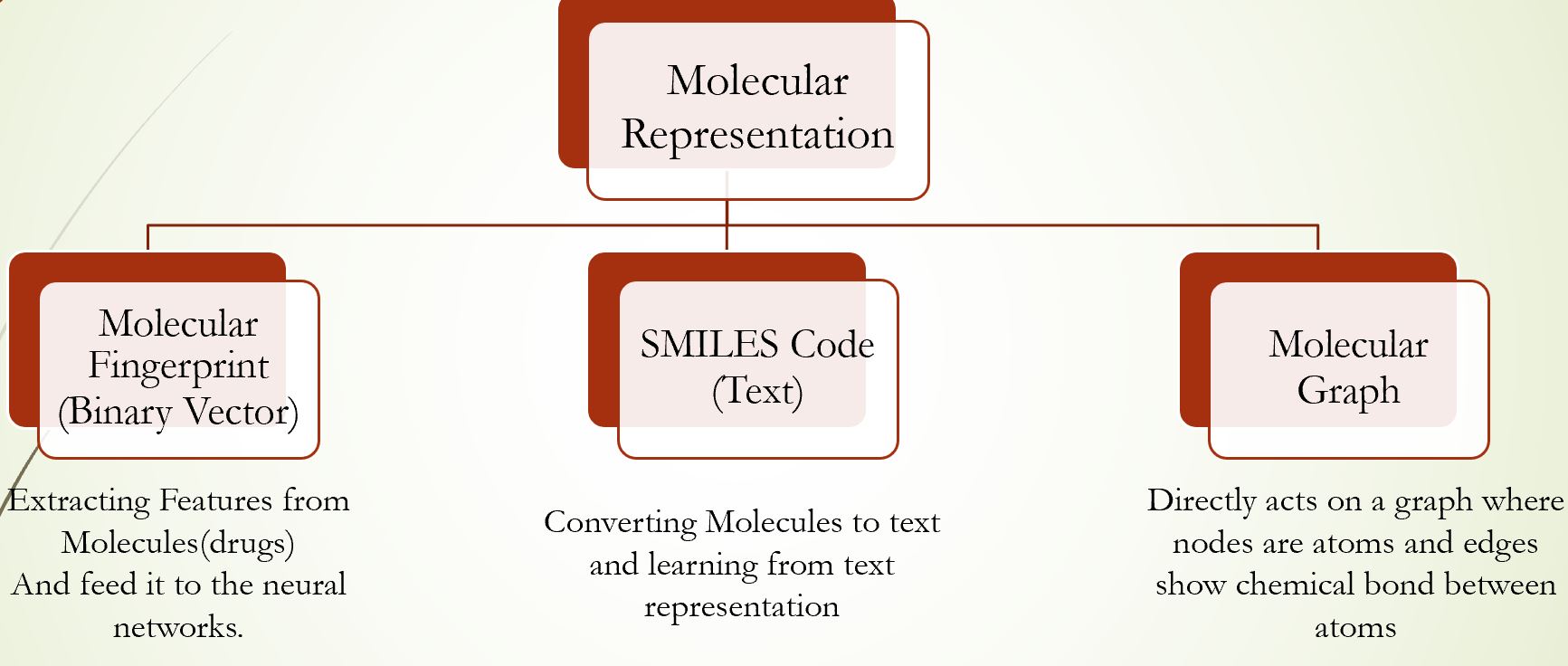

Therefore, there are different ways to represent a drug (compound):

- Molecular fingerprint

- Text-based representation (e.g., SMILES, InChIKey, SELFIES)

- Graph structure (2d or 3d graph)

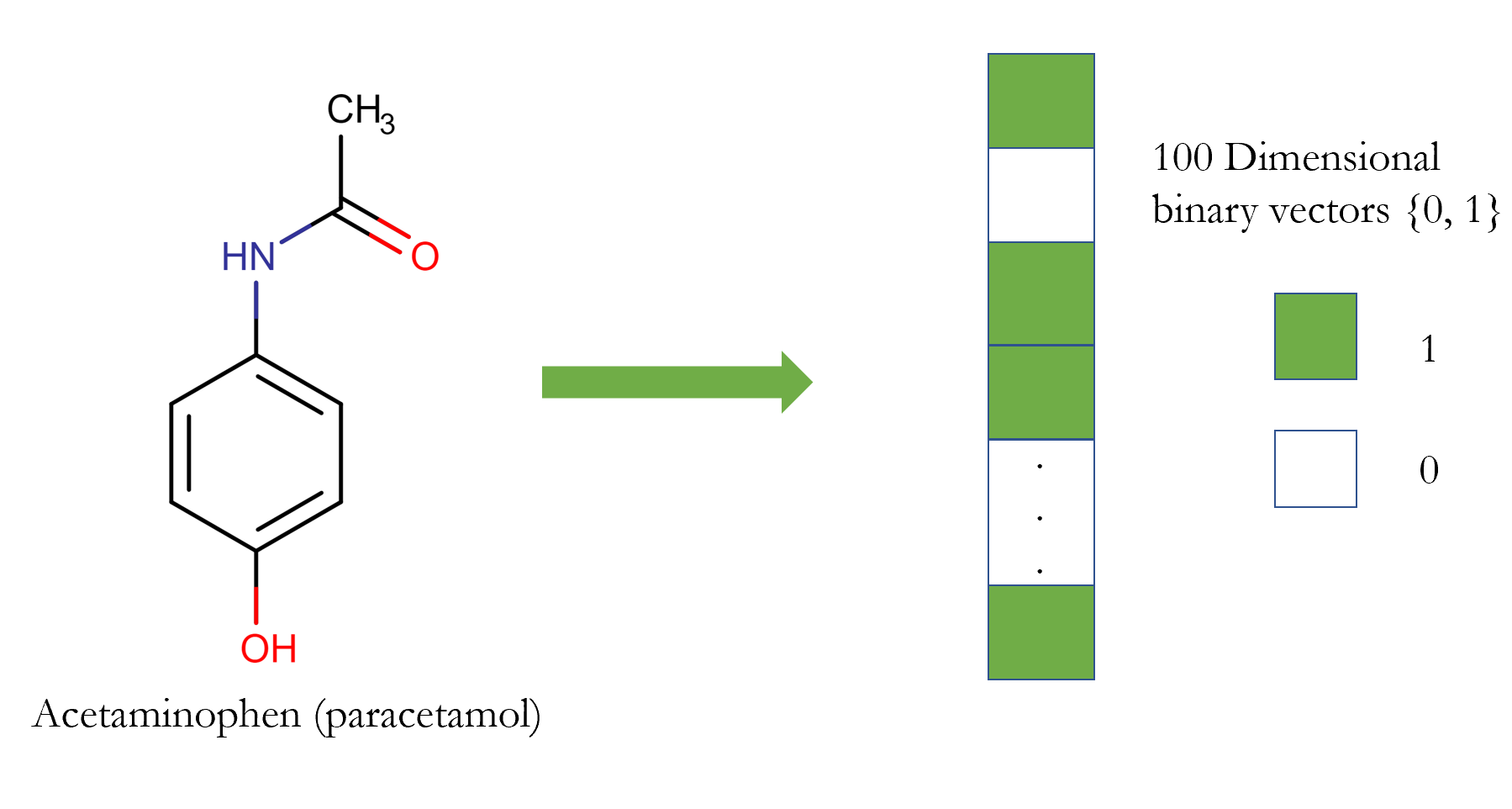

Molecular fingerprint

One way to represent a drug in the input pipeline of the machine learning framework is molecular fingerprint. The most prevalent type of fingerprint is a series of binary digits (bits) that represent the presence or absence of particular substructures in the molecule. Thus, a drug (small compound) is described as a vector (array) of zeros and ones.

It has been used extensively in the literature [1]. But, it is apparent that encoding a molecule as a vector is not a reversible process (it is a lossy transformation); i.e., we can not fully reconstruct a molecule from the fingerprint, which indicates that lots of information are lost during this operation.

There are lots of different fingerprints for representing a small molecule. You can follow this guide [2] to learn more about them.

SMILES code

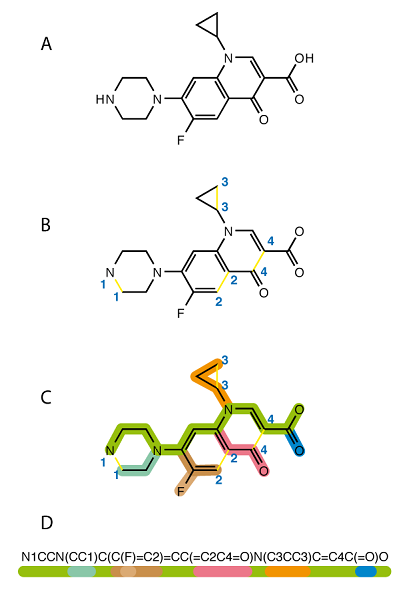

Another way to represent a molecule is encoding a structure as a text. It is the way of converting graph structure data to textual content and using the text (encoded string) in the machine learning pipeline. One of the standards and most popular representation is Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES). After conversion, we can use powerful algorithms from natural language processing (NLP) literature to process the drug and for example, predict the properties, side effects, or even chemical-chemical interaction. [Sunyoung Kwon] [3].

If you are interested to learn more about SMILES, you can follow this link [4]. Although SMILES is very popular among chemists and machine learning researchers, it is not the only text-based representation available for representing a drug. InChIKey Is another popular representation you can find in the literature. Mario Krenn et.al. [5] proposed SELFIES (SELF-referencIng Embedded Strings), which are based on a Chomsky type-2 grammar. I am talking more about them (advantages) in the De Novo Drug Design section.

Graph-structured data

Prevalence of deep learning on graph-structured data, such as graph convolution network Thomas Kipf [6], has made it possible to use graph data directly as an input to the deep learning pipeline. E.g., a compound can be considered as a graph, where vertices are atoms, and chemical bonds between atoms are edges. We have seen a significant success in the graph neural network area, and there are libraries such as Deep Graph Library, PyToch-Geometric, PyTorch-BigGraph dedicated for this work.

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

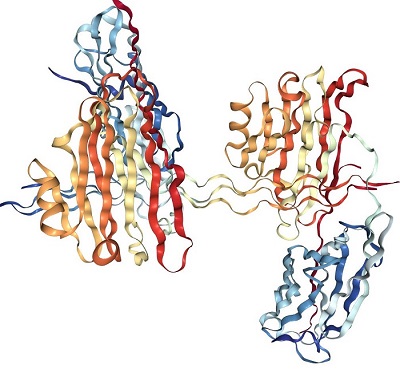

Proteins play a central role in living creatures; i.e., proteins are the key players for most of the functions within and outside the cells of living creatures. E.g., There are some proteins that are responsible for apoptosis, cellular differentiation, and other critical functions. Another important fact is, the function of a protein is directly dependent on its three-dimensional structure. I.e., changing the structure of the protein can significantly alter the functionality of the proteins, and it is one of the important facts for drug discovery. Lots of the drugs (small molecules) are designed to bind to the specific proteins, change their structure, and consequently alter the functionality. In addition, it is crucial to note that changing the function of only one protein can have a dramatic effect on cellular function. Proteins directly interact with each other (e.g., you can see protein-protein networks), and also some proteins act as a transcription factor, which means they can repress or activates the expression of other genes in the cells. Therefore, altering one protein function can have a dramatic effect on the cells and can modify a different cellular pathway.

As a result, one important problem in computational drug discovery is predicting whether a particular drug can bind to particular proteins or not. This is a concept which is called drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction and has received significant attention within recent years.

We can frame the DTI prediction task as the following:

- Description: Binary classification that predict the binding affinity of compound and protein (it can be formlized as a regression task or binary classification)

- Inputs: Compounds and proteins representation

- Output: 0-1 or a real number in $[0-1]$

Qingyuan Feng et.al. [7] proposed a deep learning-based framework for drug-target interaction prediction [7]. Most of the deep learning frameworks for DTI prediction take both compound and protein information as the input, but the difference is what representations they are using to feed to the neural networks. As I mentioned in the previous section, a compound can be represented in numerous ways (binary fingerprint, SMILES code, features extracted from graph convolution networks), and proteins as well can have different representations. Depending on the input representation, various architectures can be used to handle the DTI prediction. E.g., If we are going to use a text-based representation for both compounds and proteins (SMILES code for compound and Amino acid or other sequence-based descriptors for proteins), the RNNs based architectures are the first thing that comes to mind.

Matthew Ragoza et.al. proposed a method for Protein−Ligand Scoring with Convolutional Neural Network [8]. Instead of text-based representation, they have utilized the three-dimensional (3D) representation of a protein−ligand. Consequently, they have decided to use convolutional neural networks that can act on this 3D structure and extract meaningfull and appropriate features for predicting Protein−Ligand binding affinity.

Although it has become a great trend to propose deep learning algorithms for in-silico DTI prediction, and they have achieved to impressive results in some cases, the papers are very similar and the only innovation I found within them is the choice of input representation and subsequently, the architecture to act on the input. So, I can summarize this task as the followings:

- Finding the database that contains information about compounds and targets, and whether they are interacting with each other or not (E.g., STITCH database).

- Most often, in DTI prediction, the networks take a pair of compound and proteins as the input.

- You should choose the representation you find appropriate for compounds and proteins. I reviewed some of them, but there are other representations.

- Based on the representation you chose, you should consider suitable neural network architecture to handle the input. As a rule of thumb, you can use RNNs based architectures (GRU, LSTM, …) and transformers in case of text-based representation for inputs, and Convolutional neural networks in case of image or 3D structure.

- The problem can be considered as the binary classification (whether a compound bind to the target) or regression (prediction the strength of affinity between compound and proteins).

So, that’s it for DTI prediction. At first, maybe it seems a difficult and challenging task, but the papers I have read are using very simple techniques and strategies to tackle this problem. Moreover, if you are working on DTI prediction (or binding affinity prediction), definitely check DeepPurpose repository.

De Novo Drug Design

So far, we have just observed discriminative algorithms; i.e., given a drug, the algorithm can predict the side effect and other associated properties, or given compound-protein pairs, it will forecast whether they can bind or not. However, what if we are interested in designing a compound that has certain properties? E.g., we want to design a compound that can bind to a particular protein, modify some pathways, and does not interact with other pathways, and also have some physical property like the specific range of solubility. We can not tackle this problem with the toolkits we introduced in the previous sections. This problem is best realized in the realm of generative models. Generative models, from autoregressive algorithm, Normalizing flows, Variational autoencoders (VAEs), and generative adversarial networks (GANs), have become pervasive and widespread in the machine learning community. However, the attempts to utilize them in the task of De Novo drug design is not very old.

The problem is, generating a compound, given certain desirable properties. As it seems obvious, it is harder than the two other problems we discussed in the last sections. The space of possible chemical molecules is extraordinarily large and searching in this space to find a proper drug is very time-consuming and near-impossible tasks. I am seeing recent trends in applying generative models for designing chemical molecules. Although there are some promising results in the literature, this field is in infancy, and it requires more mature methods. Here I am going to review some of the best papers I have read in this area.

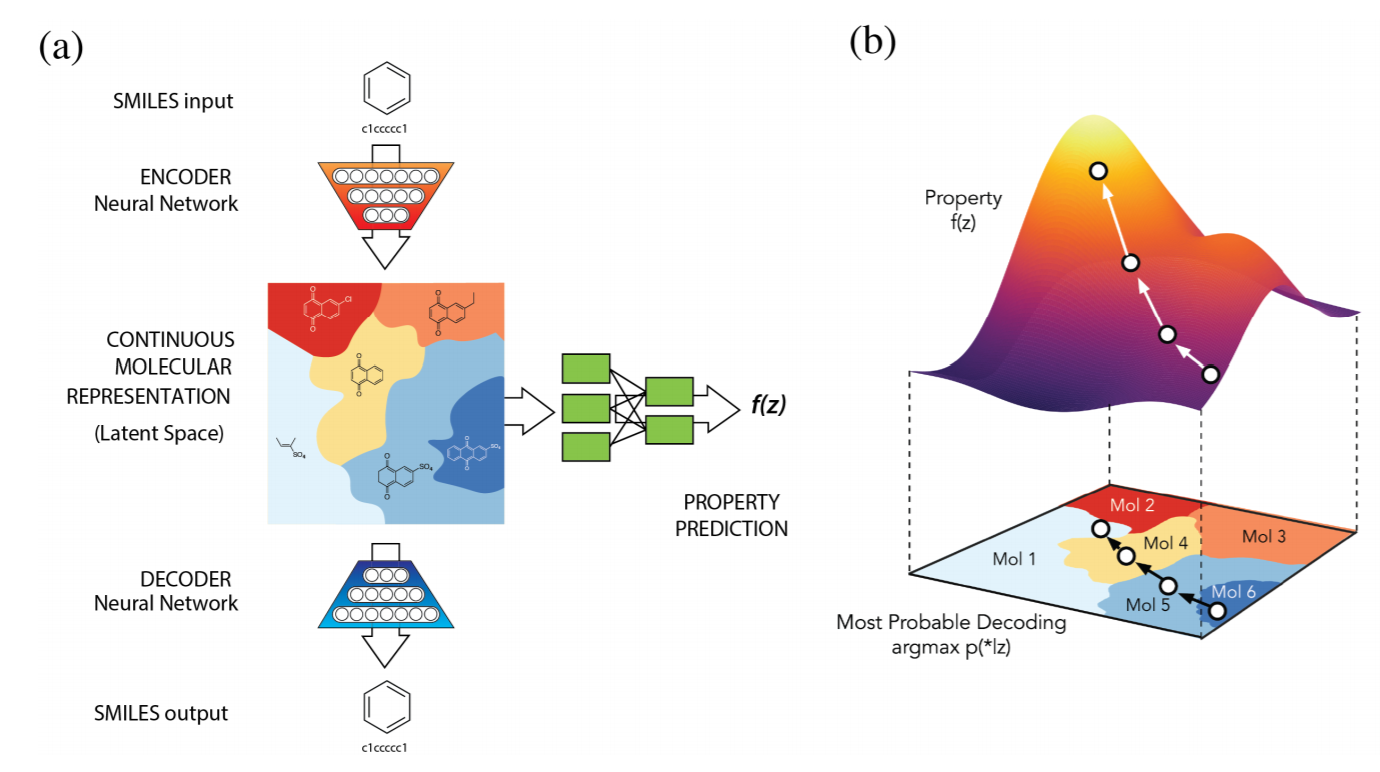

You can find a lot of paper in the literature that generates the SMILES as the output, and at the end, convert the SMILES into the chemical space. Rafael Gomez-Bombarelli et. al. proposed a method for automatic chemical design using a data-driven continuous representation of molecules [9].

They have used VAEs for generating the molecules. The input representation is SMILES code, and the output will be SMILES code too. The nice trick in the paper is using the Gaussian process in the latent space (which is a continuous space) to reach to the point with desired properties. Then, converting (decoding) this point in the latent space to the SMILES code using the decoder. The paper is well-written and definitely a recommended reading. However, The problem is that there is not a one-one correspondence between SMILES code and molecules. I.e., not all the produced code can be converted back to original (chemical) space, and as a result, the generated SMILES code often doesn’t correspond to the valid molecules.

SMILES are very popular representation, but they come with one great disadvantage: SMILES are not robust representation. I.e., changing one character (character mutation) in the SMILES can change a molecule from valid to invalid.

Matt J. Kusner et. al. proposed Grammar VAE to specifically address this issue (producing SMILES code that does not correspond to valid molecules) [10]. Instead of feeding SMILES string directly to the network and generating SMILES code, they are converting the SMILES code to the parse tree (by utilizing SMILES context-free grammar). Using the grammar, They can generate more syntactically valid molecules. Moreover, authors state that:

Surprisingly, we show that not only does our model more often generate valid outputs, it also learns a more coherent latent space in which nearby points decode to similar discrete outputs.

More recently, Mario Krenn et.el. proposed another method based on VAE and SELFIES representation [5]. The main advantage of the SELFIES is the robustness.

But, these are small samples of the works in the area of deep learning for generating a small molecule. Based on the representation of the compound (SMILES, SELFIES, Graph, …), and the algorithm for the generation (VAE, GAN, Normalizing Flow, Genetic algorithms) you can find diverse approaches in the literature (next table).

| Method | Input (output representation) | Algorithm (Model) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Character VAE [9] | SMILES | VAE | Bayesian optimization on the latent space |

| Grammar VAE [10] | Grammar rules from SMILES | VAE | Producing more grammatically valid SMILES |

| ORGAN [11] | SMILES | GAN + RL | 1. Reconciling GAN with RL. 2. Based on SeqGAN |

| JT-VAE [12] | Fragments | VAE | Packing molecules into the meaningful fragments |

| GENTRL [13] | SMILES | VAE + RL | They used GENTRL to discover potent inhibitors of (DDR1) |

| AkshatKumar Nigam et al. [14] | SELFIES | GA + DNN | 1. Genetic algorithm. 2. Robustness of SELFIES |

| Synthesizable Molecules [15] | Fragments | VAE | 1. Focus is on the synthesizability 2. Provide synthesis route |

Conclusion

In this post, I tried to review some of the applications of deep learning in drug discovery. Clearly, this review is not complete, and I did not have time to cover more areas (and I did not want to make this post longer), but I tried to provide references for curious readers. I hope this post encourages you to contribute to this area for making drug discovery less-expensive and less tedious work.

References

- Database fingerprint (DFP): an approach to represent molecular databases, Eli Fernández-de Gortari et al.

- Fingerprints in the RDKit

- DeepCCI: End-to-end Deep Learning for Chemical-Chemical Interaction Prediction, Sunyoung Kwon

- OpenSMILES specification. link

- SELFIES: a robust representation of semantically constrained graphs with an example application in chemistry, Mario Krenn et al.

- GRAPH CONVOLUTIONAL NETWORKS, Thomas Kipf

- PADME: A Deep Learning-based Framework for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction, Qingyuan Feng et al.

- Protein–Ligand Scoring with Convolutional Neural Networks, Matthew Ragoza et al.

- Automatic Chemical Design Using a Data-Driven Continuous Representation of Molecules, Rafael Gomez-Bombarelli et al.

- Grammar Variational Autoencoder, Matt J. Kusner et al.

- Objective-Reinforced Generative Adversarial Networks (ORGAN) for SequenceGeneration Models, Gabriel Guimaraes et al.

- Junction Tree Variational Autoencoder for Molecular Graph Generation, Wengong Jin et al.

- Deep learning enables rapid identification of potent DDR1 kinase inhibitors, Alex Zhavoronkov et al.

- Augmenting Genetic Algorithms with Deep Neural Networks for Exploring the Chemical Space, AkshatKumar Nigam et al.

- A Model to Search for Synthesizable Molecules, John Bradshaw et al.

Leave a comment